Participatory civic design: You can do it, too!

The folks behind the Manresa Island project are holding public feedback sessions as they finalize their master plan for the site.

View this post on Linkedin here.

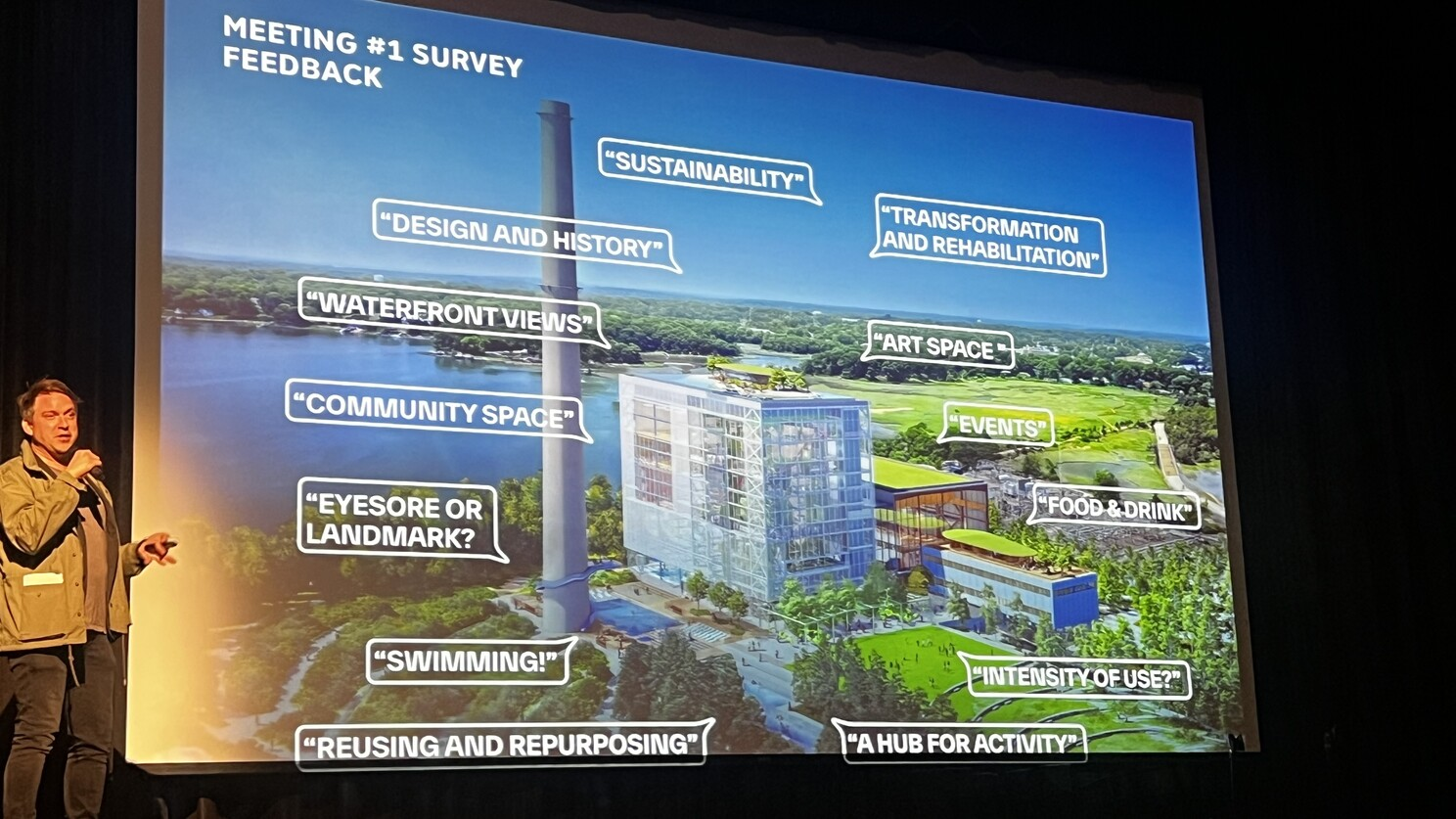

You can always find Norwalk when you look across Long Island Sound toward the Connecticut coastline—just look for the big smokestack. That's the defunct Manresa Island power plant, shut down decades ago and passed from hand to hand ever since as various developers failed to invest in the cleanup it needed.

Then the McChords came along—the quintessential philanthropists who call Norwalk their hometown—and they decided, after a kayak ride around the island, that it was time for this island to get the glow-up it badly needed—and they were going to commit to making it happen. And they wanted to go all the way, making it a public park for the whole community to enjoy.

Turning an abandoned power plant that happens to take up a big chunk of valuable public coastline into a public park sounds like an easy win (while still being an enormous investment and challenge)—but when it comes to publicly engaging folks in a big project that could affect how their city works, everyone's going to want to have a chance to have their voice heard.

Which is why the folks behind the Manresa Island project are holding public feedback sessions as they finalize their master plan for the site.

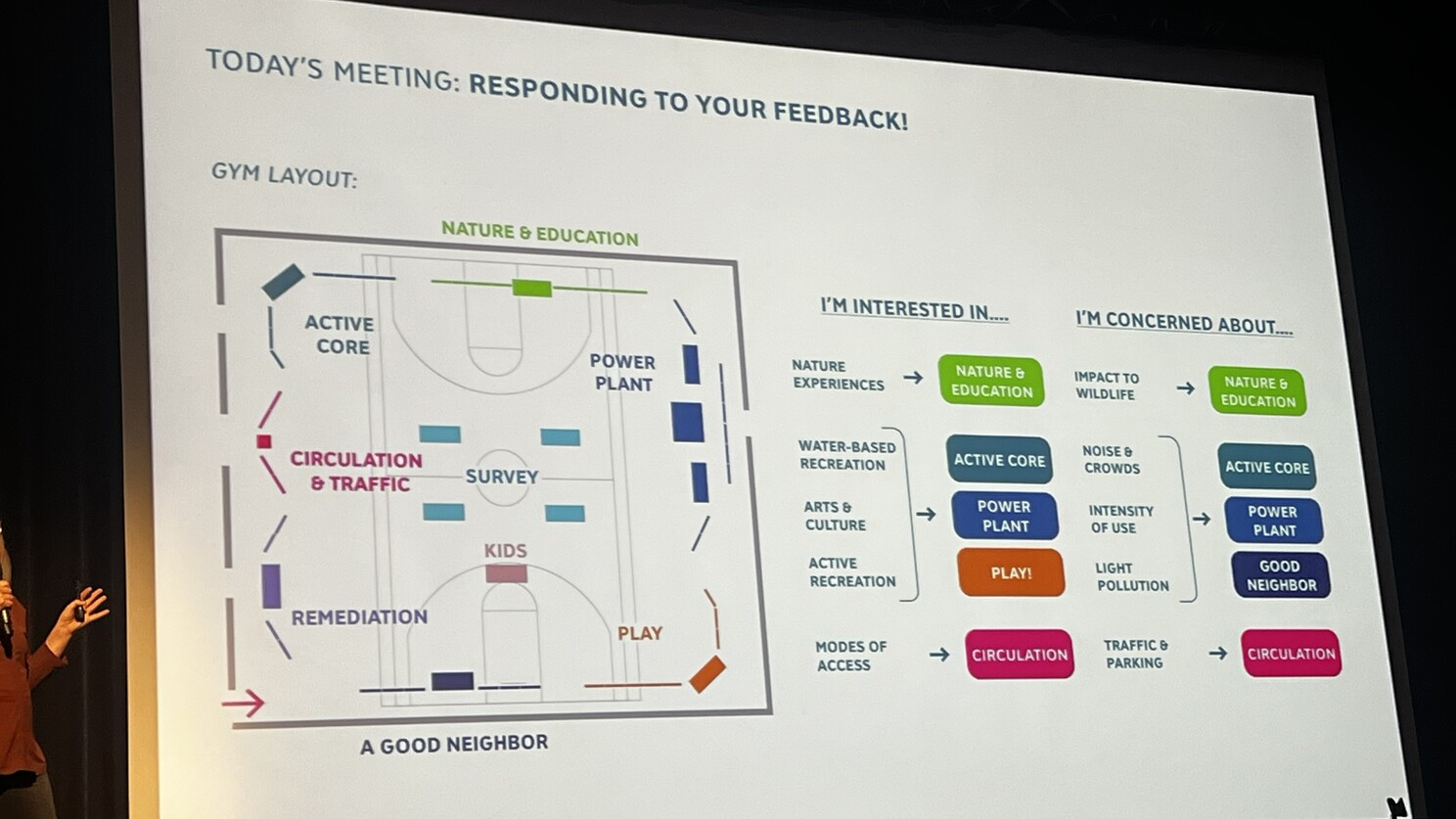

It started as expected, with a slide show making the case for the project. Members of partner firms SCAPE Landscape Architecture DPC, BIG - Bjarke Ingels Group, Tighe & Bond and others presented alongside executive director Jessica Vonashek.

The second part of these sessions was what blew me away.

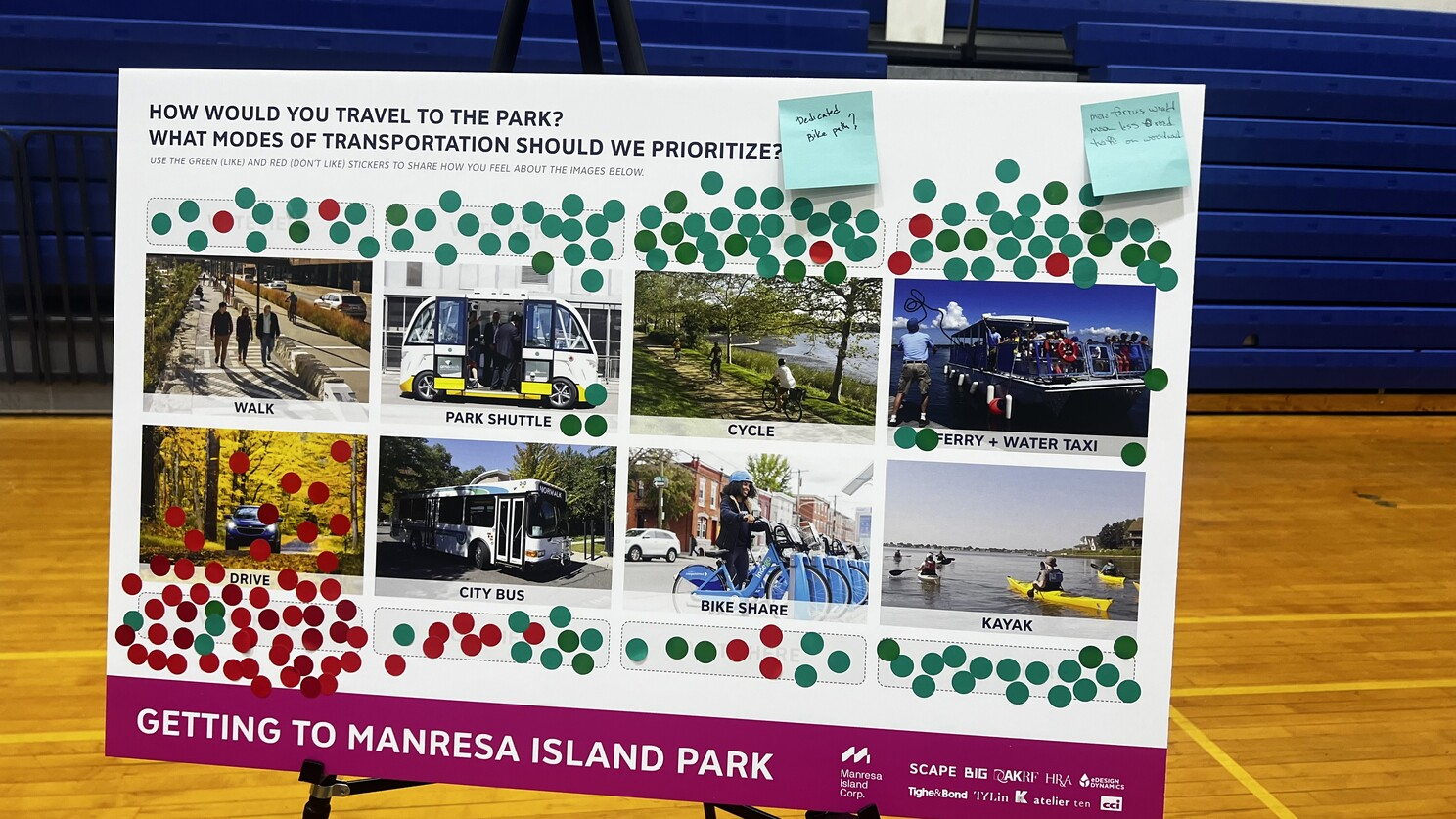

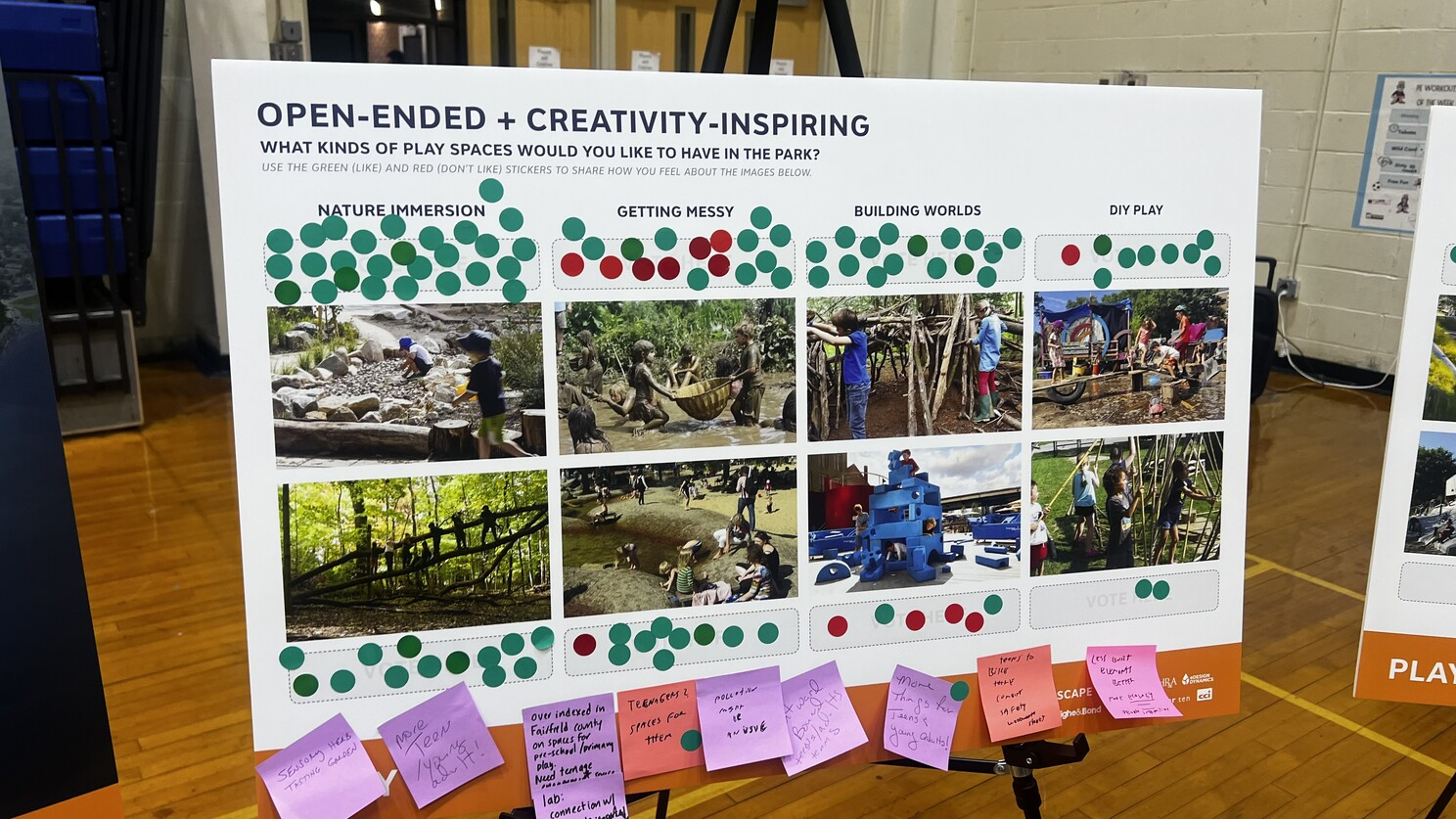

For this portion, we transitioned from the high school auditorium to the gym—which was set up with a giant circle of boards on easels, depicting different proposed aspects of the project.

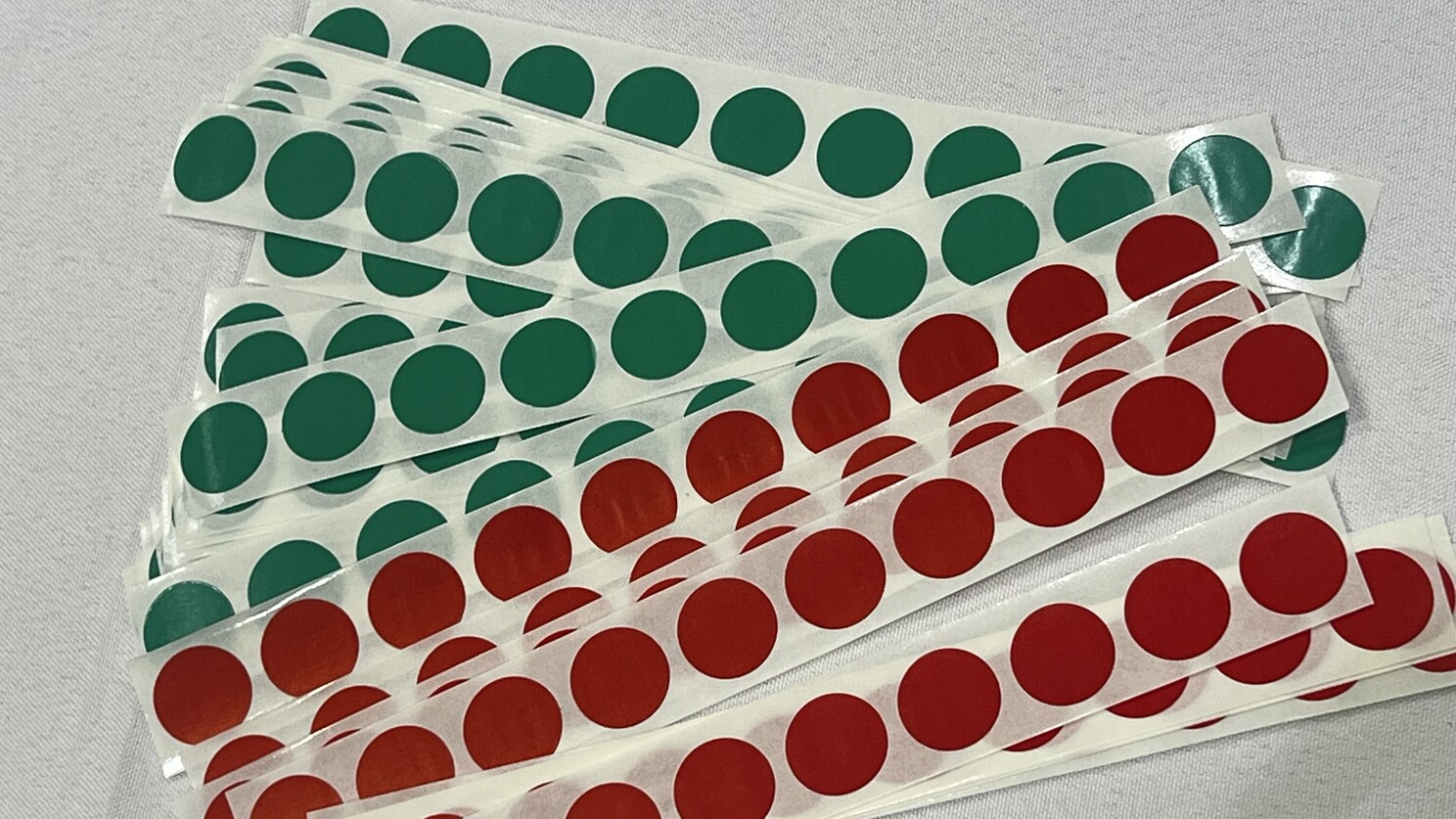

Every person who walked into the gym was handed two strips of circle stickers—one red, one green.

As we were given these, we were instructed to place the colored dots on the things we felt positively or negatively about.

Almost immediately I heard someone nearby tell their friend "they're gonna need to give me more red dots" 🙂

I can't get over how cool this is.

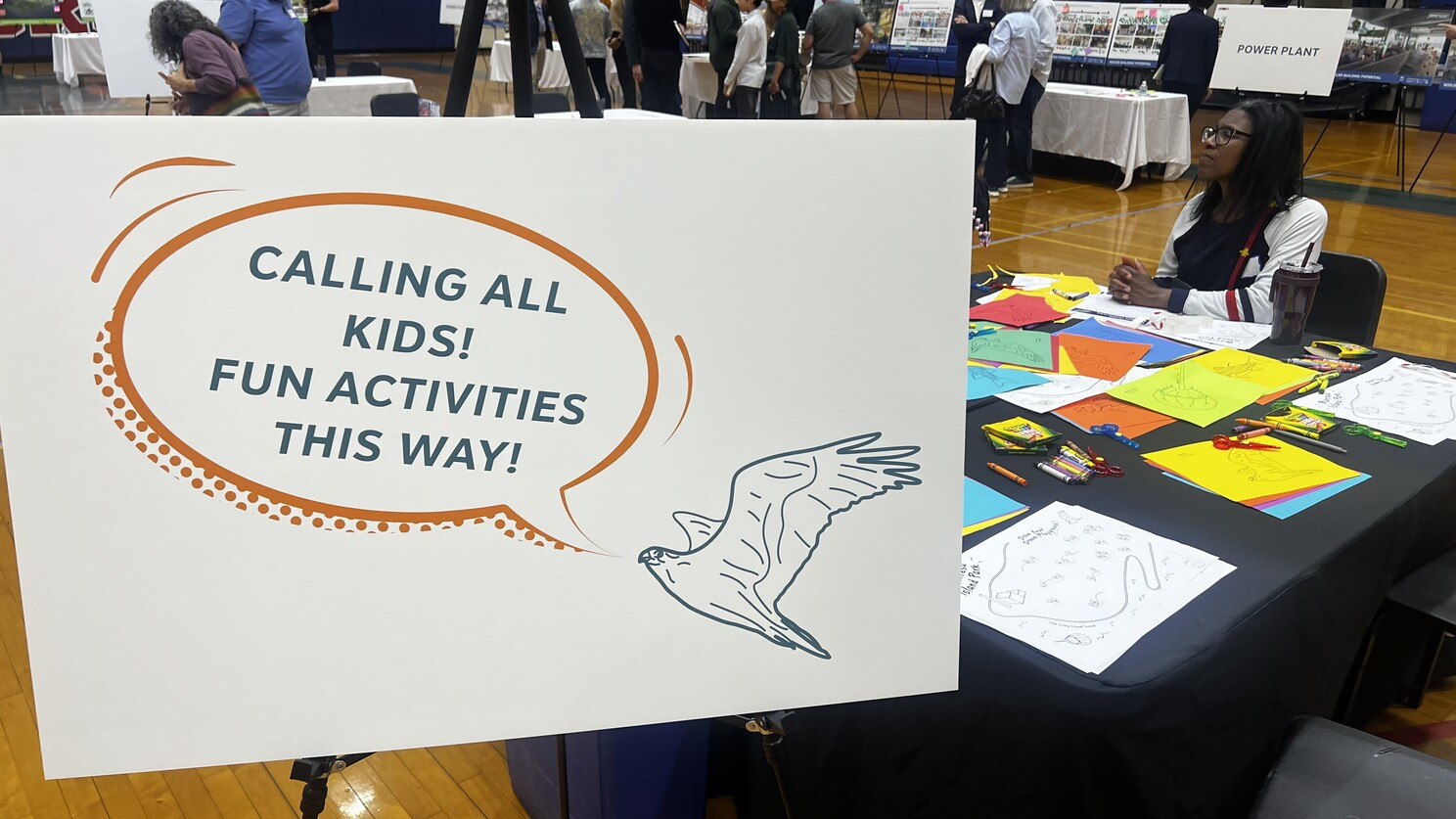

The layout was broken up into different sections based on different aspects of the project—the environment, activities for kids, nature, events, transportation, etc—and at least one member of the team was posted to each station, available to answer questions and engage in discussion.

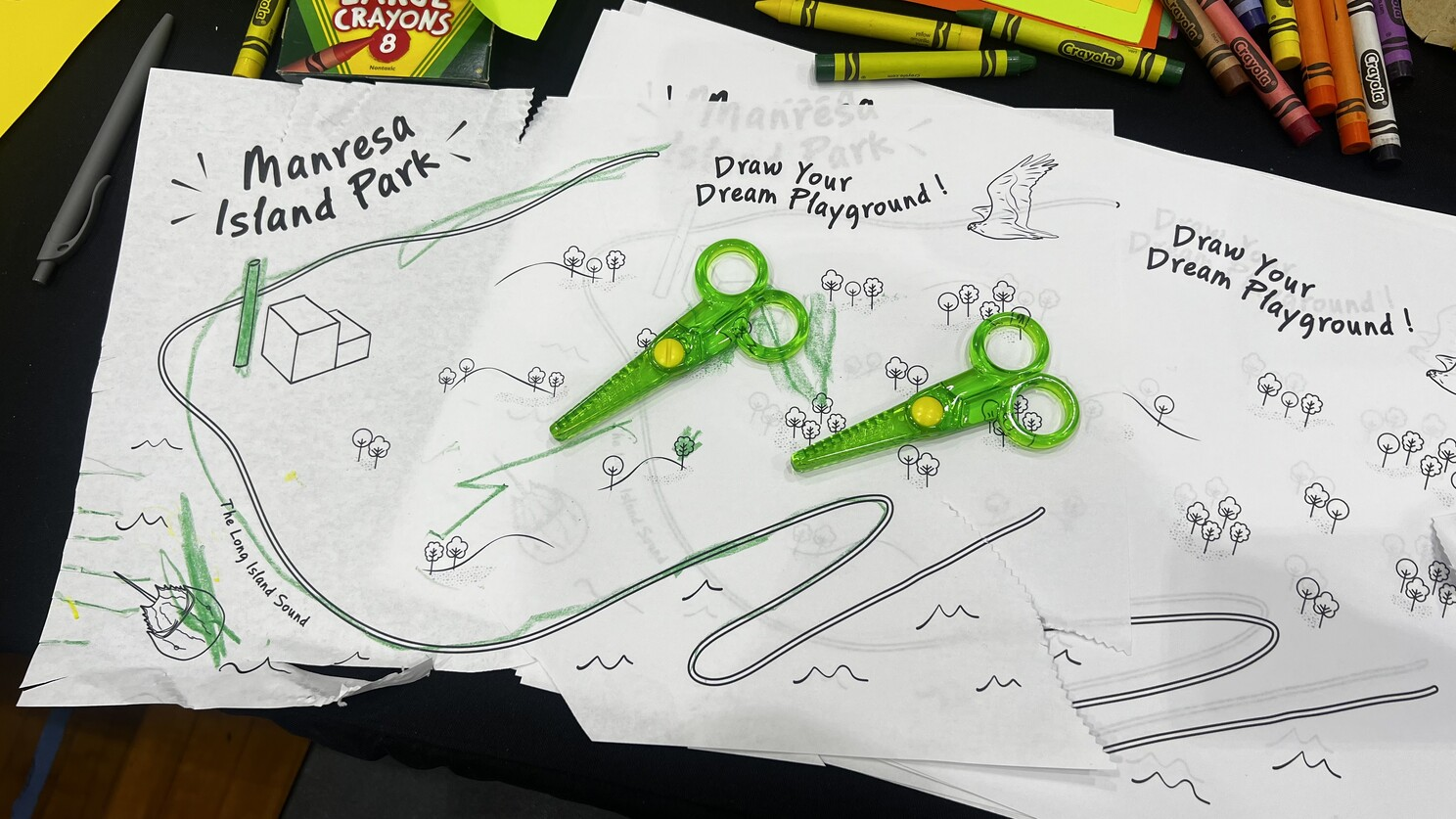

Oh, and in the middle, a section for kids! How thoughtful!

People dove in. The stickers piled up with lightning speed—and while this method, sometimes called Dot Voting or Dotmocracy, carries some doubts as to the veracity of the data it generates, it's a damn powerful way to get people involved and talking.

I saw it over and over—one person would place a sticker, another would place a sticker too—maybe the other color—and they'd start talking about it. I saw people learning others' perspectives in real time. It was magical.

At the end of the day, even if the project moves forward in ways not everyone is fully supportive of, the people in that room felt like they were a part of the process and that their perspective was valued and considered.

And the organizers, of course, come away with powerful data to guide their priorities as they finalize their plans.

Public engagement is more than a little tricky to get right—some even suggest most public engagement is worse than nothing at all—but the value of getting it right can't be overstated.

While this project is huge and well-funded, participatory design is extremely accessible to any project that can scrounge up some poster boards, easels, and colored dots.

If you see an opportunity to run something like this for a project you're involved with, let me know.

Tony Bacigalupo

Tony Bacigalupo